| |

|

|

02.

| Face - 99 names of God |

| |

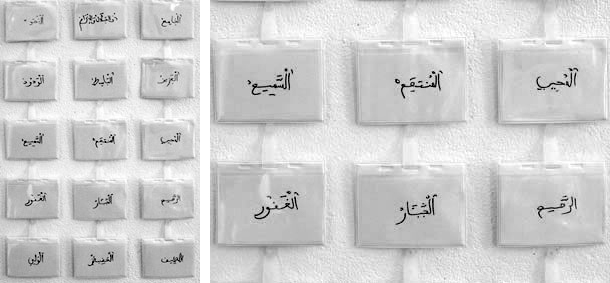

1999, 99 badges, names.

Exhibition view from Face, les 99 noms de dieu, Galerie Saint Séverin, 2006, Paris.

Courtesy of the artist and Lawrie Shabibi, Dubai.

Ed. of 5 + 1 A.P.

'' Faced with these 99 names, we each imagine a different God. Even if we cannot decipher the language, the written word retains its sacred value. ''

mounir fatmi, 1999

Face - 99 names of God

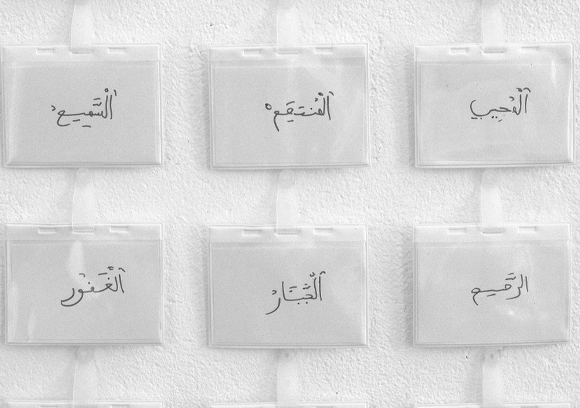

Exhibition view from Face, les 99 noms de dieu, Galerie Saint Séverin, 2006, Paris.

Courtesy of the artist.

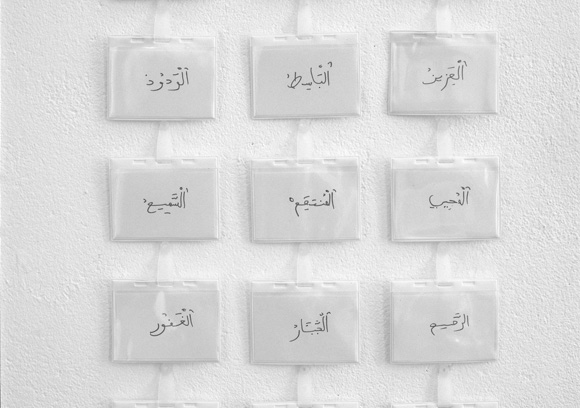

Face - 99 names of God

Exhibition view from Face, les 99 noms de dieu, Galerie Saint Séverin, 2006, Paris.

Courtesy of the artist.

|

|

|

|

|

|

L’art musulman n'a produit aucune image de Dieu, la religion interdisant sa représentation. Il est évoqué dans le Coran par 99 noms tels le Superbe, le Créateur, le Formateur ou le Tout et Très Contraignant. Dans cette proposition, le public se trouve confronté à ces noms écrits sur des badges de conférence. Ainsi c'est malgré tout à travers une image que chaque spectateur s'imagine intérieurement Dieu. La richesse par rapport à l'image qui aurait pu être montrée ne fait pas de doute.

Chacun alors s'imagine Dieu différemment.

Même indéchiffrable l’écrit garde ainsi sa valeur sacrée, et fait danser le corps de ses lettres sur un mur de silence où s’inscrivent les quatre-vingt-dix-neuf noms d’Allah (les bédouins disent que seul le chameau détient le nom du centième). En tant qu’artiste, j’appuie en même temps sur la perte d’orientation du religieux qui passe par la question particulière de la Qibla (direction de la Mecque) et sur la perte d’un centre en général. »

Mounir Fatmi, 1999.

La question des noms du divin est commune à la plupart des religions. Pour les chinois le mot Dao est le pseudonyme de l’ineffable. Lao Zi écrit : » Voie qu’on énonce n’est pas la voie - nom qu’on prononce n’est pas le nom ». Cette attitude se retrouve dans le judaïsme ou le nom de Dieu révélé à Moïse était prononcé une fois, lors du nouvel an par le grand prêtre et ne l’est plus depuis la destruction du Temple. Chez les auteurs chrétiens, la méditation sur les noms divins dit quelque chose de l’être de Dieu tandis que pour L’Islam les noms de Dieu renvoient à des attributs mais la réalité même de Dieu est indicible. L’attention portée par toutes les grandes mystiques à cette question pose la question de notre Relation avec Dieu, lien si intime qu’il touche à la sanctification ou à la profanation de son Nom par nos actes.

Dans le Coran, un mot sur vingt environ fait mention expresse de Dieu par l’un de ses noms. On n’oublie jamais Celui à qui revient la soumission (islâm) de tout. L’œuvre de Mounir Fatmi fait allusion au fait que ces noms sont arborés par les musulmans qui les portent sous la forme connue : àbd al Qâdir (Serviteur du Puissant) ou Abdallah= Àbd Allâh (Serviteur de Dieu). Dans le monde d’aujourd’hui on peut imaginer une conférence, ou chacun, « badgé » participerait à l’énonciation des 99 Noms. Ainsi l’artiste, pose à la fois la question de notre responsabilité à l’égard de ces Saints Noms et l’ambiguïté de leur apparition dans notre univers moderne.

Jean de Loisy, 2006,

Galerie saint Séverin, Paris

|

|

“Islamic art has produced no image of God, as the religion prohibits His representation. In the Koran, 99 different and highly imagistic names evoke God: The Magnificent, The Creator, The Fashioner of Forms, The Ever Enduring and Immutable… In this piece, the public is confronted with 99 conference badges inscribed with these evocative names. Thus, through a subtle sleight of hand, the spectator conjures up an image of God, images that are surely even richer than if God had been pictured.

Faced with these 99 names, we each imagine a different God. Even if we cannot decipher the language, the written word retains its sacred value – the body of the letters dance on a wall of silence forming the ninety-nine names of Allah (the Bedouin say that only camels know the one-hundredth name.) As an artist I am interested in the loss of orientation that the faithful can face (this includes the question of Qibla, the direction of Mecca), as well as the loss of center in general.”

Mounir Fatmi, 1999.

The preoccupation with how to name the Divine is shared by most religions. For the Chinese, the word Dao is an alias for the ineffable. Laozi writes, “the Way that can be spoken of is not the eternal Way, the name that can be named is not the eternal name.” This idea is also found in the Jewish tradition: the name of God is revealed to Moses only once, on the new year, then never again following the destruction of the Temple. When Christian writers meditate on divine names for God they are describing His attributes, while in the Islamic tradition the names for God describe attributes but the very reality of God’s existence remains unsayable. The attention that the greatest mystics have paid to this question calls into question our relationship with God, a connection so intimate that our acts can either sanctify or profane his name.

In the Koran, one out of twenty words expressly mentions God by one of his names. We never forget He to whom all things are obedient. Mounir Fatmi’s work makes allusion to the Muslims whose given names are inherited from these divine attributes: àbd al Qâdir (Servant of the All-Powerful) ou Abdallah= Àbd Allâh (Servant of God). In today’s world we can imagine a conference where the attendees, wearing badges, participate in a roll-call of the 99 Names. Thus the artist questions both our individual responsibility to these Holy Names, and the ambiguity of their place in our modern universe.

Jean de Loisy, 2006,

Galerie saint Séverin, Paris

|

|

|

|